The Colourful Question

The colours of the planets in our Solar System are more than just eye candy — they offer real clues about the chemical makeup and surface properties of each world. From the rusty red of Mars to the deep blues of Neptune, these differences aren’t random. They reflect how light interacts with each planet’s atmosphere (or lack thereof), surface material, and distance from the Sun.

Yet, what we see from Earth isn’t always what a planet truly looks like up close. Telescopes, space probes, and even our own atmosphere all influence how colours are perceived.

Let’s uncover the true hues of each planet — and the science behind what we see.

Mercury: The Quiet Grey

Mercury is a rocky, cratered world with a surface composed mainly of iron, nickel, and silicate rock. With no significant atmosphere to scatter or filter sunlight, Mercury appears grey from all perspectives — whether you’re looking at it through a telescope or standing on its surface. Its resemblance to our Moon is no coincidence; both are ancient, atmosphere-free surfaces shaped by billions of years of impacts.

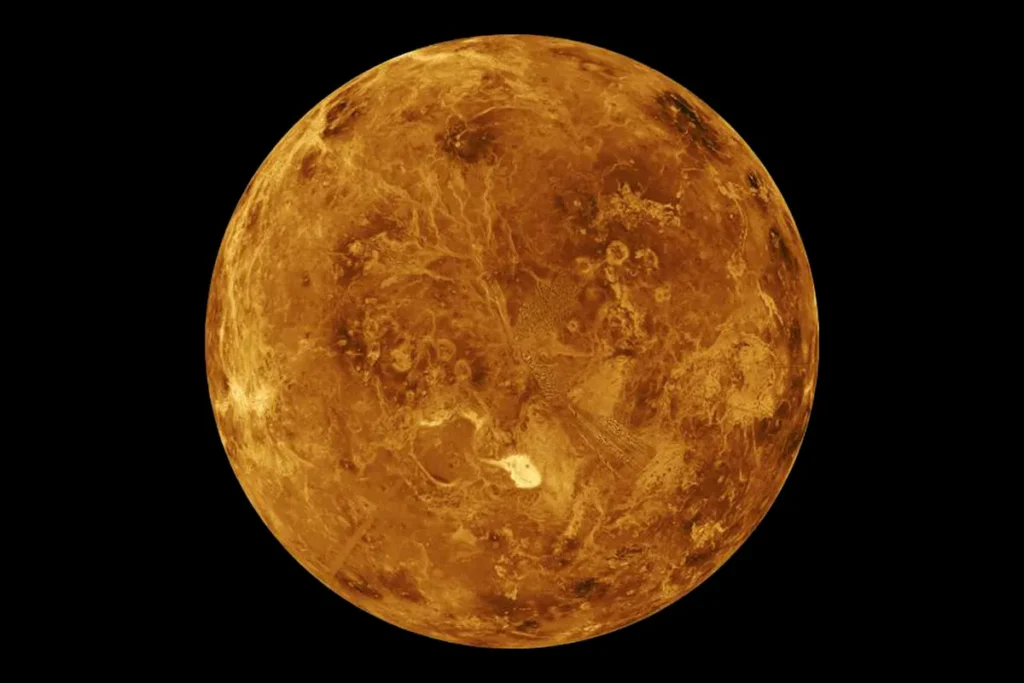

Venus: Yellow Through the Clouds

Though its surface is rocky and grey like Mercury’s, Venus appears pale yellow or golden when seen from Earth. Why? Its thick atmosphere is packed with clouds of sulfuric acid that absorb blue and violet light, allowing only longer yellow and red wavelengths to reflect back to us. Therefore, despite the dullness of the rocks beneath, the visual effect observed from space appears as a hazy golden veil. Venus’s light-scattering atmosphere is an excellent reminder that we often don’t see a planet’s surface at all — only the gases above it.

Earth: The Blue Marble

Earth’s vibrant blue hue is the result of Rayleigh scattering, where particles in the atmosphere scatter shorter (blue) wavelengths of sunlight more than longer red ones. Our oceans also reflect this blue light, reinforcing Earth’s nickname as “The Blue Planet.” From space, white cloud patterns, green and brown continents, and vast oceans combine to create a planet teeming with life and colour. It’s no wonder Earth is the baseline by which we compare all others.

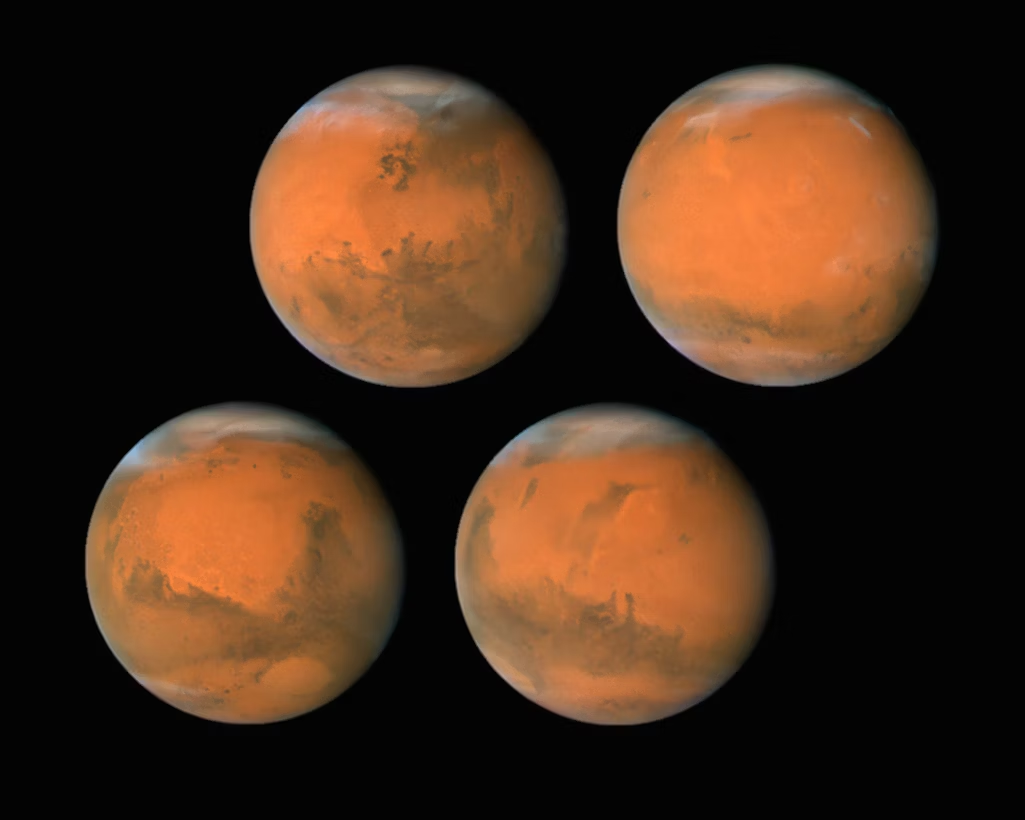

Mars: Rusted and Red

Mars is famously known as “The Red Planet” — and the name holds up. The Martian surface contains iron oxide (rust), which gives it a distinctive reddish-orange hue. Because its atmosphere is so thin, the rusty surface is visible even from afar. The combination of its dusty terrain and weak atmospheric filtering means that the red colour we see from Earth is quite accurate.

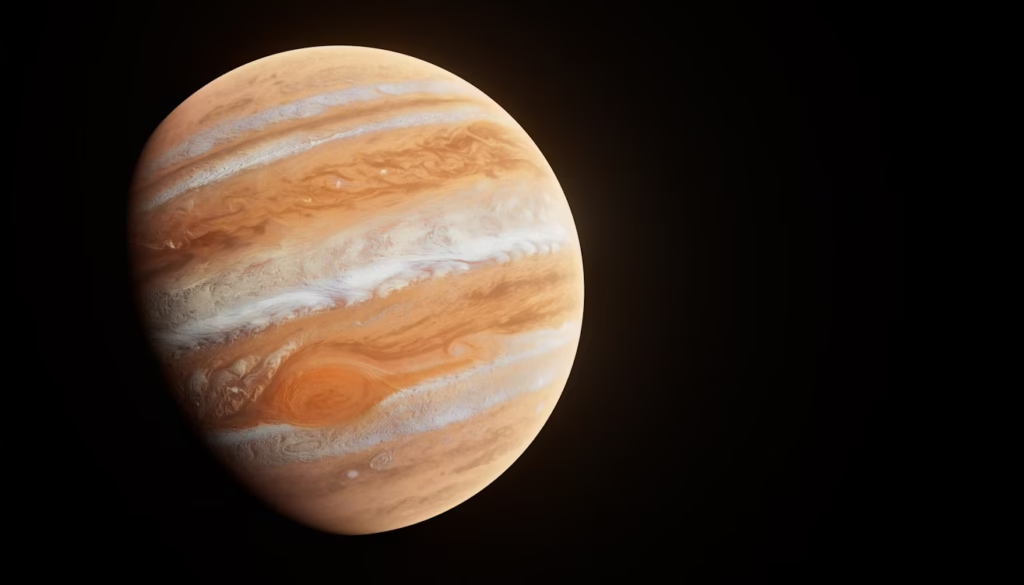

Jupiter: Striped in Browns and Reds

Jupiter is a swirling, massive gas giant without a solid surface. Its atmosphere is made up of layers of hydrogen, helium, ammonia, and other compounds that form colourful bands across the planet. These bands vary in colour — from light tan and yellow to deeper browns and rusty reds. The Great Red Spot, a centuries-old storm, adds a bold splash of crimson. The planet’s dynamic weather systems churn its clouds into a constantly changing palette.

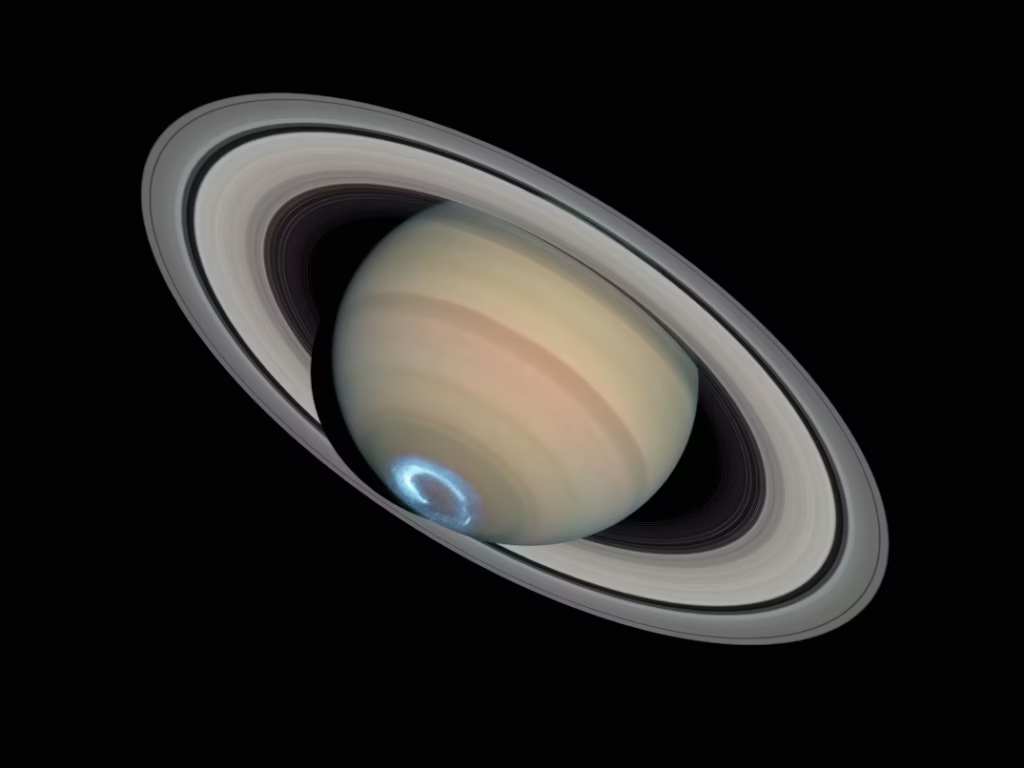

Saturn: The Pale Beauty

Saturn has a more muted appearance than Jupiter. While still a gas giant, its cloud layers show less contrast. Its colours range from soft yellows and creams to occasional greys. The planet’s famous rings, made of ice and rock, also contribute to its lighter, pastel look. Saturn’s beauty lies in its subtlety — a smooth, glowing orb ringed with reflective brilliance.

Uranus: The Cyan Giant

Uranus appears pale blue or cyan due to methane gas in its upper atmosphere. Methane absorbs red light while reflecting blue, giving the planet its icy look. Interestingly, Uranus’s colour is more uniform than that of other gas giants, likely because of its calmer atmosphere and minimal storm activity. From a distance, it resembles a smooth blue-green marble floating in the void.

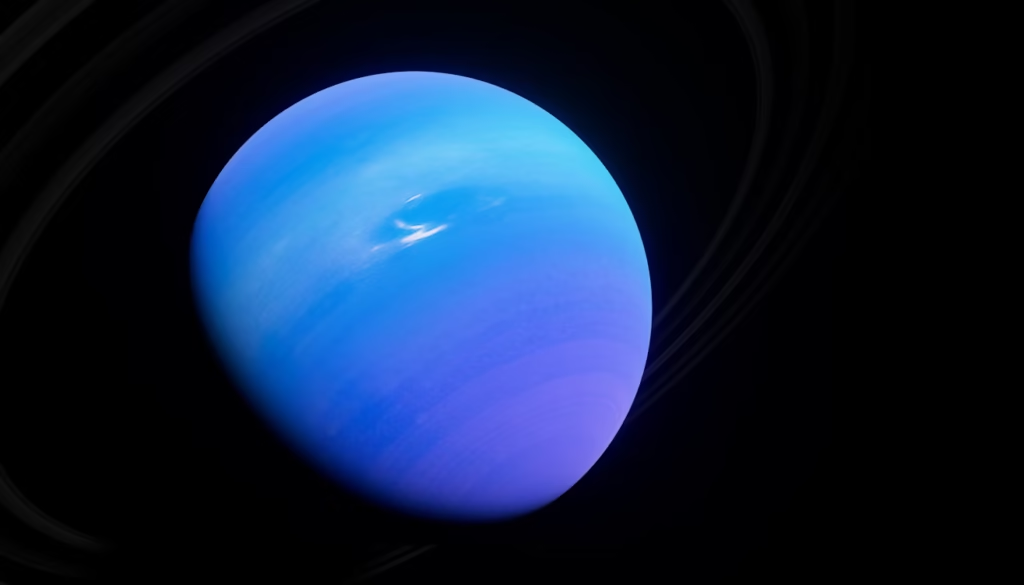

Neptune: Deep and Stormy Blue

Neptune is similar to Uranus in composition, but its darker blue shade is more intense. Like Uranus, it contains methane that filters out red light. However, additional atmospheric components and stronger internal heat may intensify its colour. Bright white clouds — made from methane ice — can often be seen against its darker background, especially during large storm outbreaks. Neptune is the most vibrantly blue world in our Solar System.

Pluto: Earth Tones at the Edge

Though reclassified as a dwarf planet, Pluto also has a colour signature worth noting. Images from NASA’s New Horizons mission show it has large patches of dark red, grey, and brown. These colours are caused by frozen methane and nitrogen interacting with sunlight and forming complex molecules called tholins. Despite its distance from the Sun, Pluto’s patchy surface reveals it to be a visually diverse and dynamic world.

Planet Colour Comparison Table

While we’ve explored the colours of each planet in paragraph form, here’s a quick summary for reference:

| Planet | Colour | Main Cause |

| Mercury | Grey | Rocky surface (no atmosphere) |

| Venus | Yellow | Sulfuric acid clouds |

| Earth | Blue, green | Oceans, sky scattering, vegetation |

| Mars | Red | Iron oxide (rust) |

| Jupiter | Brown, red | Gas bands and ammonia clouds |

| Saturn | Yellow-grey | Pastel clouds and icy rings |

| Uranus | Pale blue | Methane absorption |

| Neptune | Deep blue | Methane + unknown absorbers |

| Pluto | Grey-brown | Frozen nitrogen + tholins |

Light, Atmosphere, and Perception

So what exactly determines the colours of the planets?

It all comes down to how light interacts with each planet’s unique environment.

- Scattering: Gases like nitrogen or methane scatter certain wavelengths more than others. This is why Earth is blue, and Uranus and Neptune appear blue too.

- Absorption: Some elements absorb specific light frequencies — for instance, methane absorbs red light, allowing blue to shine through.

- Surface Composition: Rocky surfaces reflect light differently than cloud tops or icy rings. Dust, metals, or ices all impact reflectivity and colour.

Understanding how light behaves is also key to other astronomical principles — such as how we measure distances in space. For a deeper explanation of this, check out our guide on Parsec 3.26 Light Years — which explains how parallax and light define distance.

More Than Just Colour: Planetary Identity

The colours of the planets are just one way we perceive their character. But there’s another: sound. While space is a vacuum, spacecraft can measure plasma waves and convert them into audible sound. NASA’s Cassini mission, for example, captured remarkable audio while flying past Saturn.

If you want to hear what space “sounds” like, especially near gas giants, we recommend exploring the sounds of space — a fascinating bridge between sight and sound in space science.

Final Thoughts

Planet colours aren’t just visuals — they’re science. Each one tells a story: of atmospheres, elements, weather systems, and sunlight. The next time you look up at Mars glowing red or Venus shining like a golden star, you’ll know the physics behind the beauty.

Understanding the colours of the planets helps us interpret what we see through telescopes — and deepens our connection to the worlds beyond our own.

Share this content:

Post Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.